William B. Cassidy, Senior Editor | Aug 10, 2020 5:35PM EDT

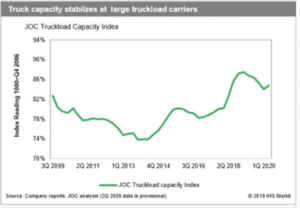

Large truckload carriers put the brakes on capacity cuts in the second quarter, keeping their truck counts flat after four quarters of trimming, according to preliminary JOC.com Truckload Capacity Index (JOC TCI) data. The index’s preliminary reading of 84.8 is a bump up from the final first-quarter reading of 84 but is flat when a “same fleet” analysis is run on the data. The results indicate large, publicly owned truckload carriers held onto capacity when they could as freight demand returned in May and June after plummeting in April. With their ability to field large numbers of trucks, those carriers benefited when truckload capacity tightened overall, especially in June and July, as increased demand collided with supply chain disruption.

Large carriers will not be quick to add capacity, despite rising demand. “In order to add additional capacity, there is a cost of doing so and especially right now,” Derek Leathers, chairman, CEO and president of Werner Enterprises, said during a July 29 earnings call. “I can’t overstate some of the issues going on in the supply side (as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic).”

For one, Leathers claimed truck drivers who are already near retirement age are accelerating their exit plans, and there are fewer new entrants. Licensing agencies across the US issued 100,000 fewer commercial driver licenses in the first six months of the year, and truck driving schools are producing about 60 percent of the graduates they did prior to the pandemic, he said.

“I don’t know anybody who feels they’re getting as many trucks as they wish they could get right now,” David Jackson, president, and CEO of Knight-Swift Transportation Holdings, told JOC.com, adding “there’s been massive attrition in supply”, especially labor. Trucking lost 92,000 jobs from February to April, and has only regained 42,500 of them, US data show. Several factors caused the trucking supply to contract sharply at the end of the second quarter. A rebound in consumer demand and sales is one, but the contraction may owe as much to supply chain disruption and dislocation of assets and labor during the COVID-19 pandemic. And government stimulus supported consumer spending that swung heavily to physical goods.

Capacity is king, again

Within three months, the trucking industry lived through an entire pricing cycle, said Geoff Muessig, chief marketing officer of Pitt Ohio, a regional less-than-truckload (LTL) and truckload operator. “I’ve never seen a market change so fast, from ample capacity in April to tight capacity in July,” he told JOC.com, adding consumer demand is spurring industrial production and freight.

“It’s not all retail. Bicycle helmets are flying off shelves, and that means demand is way up for the composites that are used to make those helmets,” Muessig said. Pitt Ohio has more exposure to those composites and other materials used in the industrial production of consumer goods than to big-box retailers, and the carrier sees no lack of available freight. Capacity is king again, at least for the moment, and the trucking company that has it, as well as the shipper that gets it, wins. It is unclear how long the atypically tight summer market will last. Some, including Jackson, see a demand curve that continues to climb. Others see a bumpier ride ahead, thanks to COVID-19 and high unemployment.

“I think there’s a pretty good demand runway over the next two or three quarters,” Jackson said. That is partly owing to consumer spending, but also to supply chain disruption that is causing businesses of all types to scramble to catch up with weeks or months of lost business. “I would dare say every supply chain in America has been disrupted and is backlogged,” he said.

Whether the US government extends stimulus payments and unemployment benefits may determine whether freight demand stays high and capacity remains tight. “We still can’t get a good feel for whether the underlying demand is going to continue,” Avery Vise, vice-president of trucking for FTR Transportation Intelligence, said during a webinar last week. “To a large degree, what we saw in May, June, and into July was underwritten by the federal government,” Vise said. “It didn’t necessarily create all that demand, but it enabled it.” The executive orders signed by President Donald Trump last weekend did not include additional stimulus payments, and reduced expanded unemployment benefits from $600 to $400 a week.

It is not even clear if those executive orders, which also include partial deferment of payroll taxes, will survive a challenge from Congress, which holds spending power under the US Constitution. Both houses of Congress have relief bills but have not agreed on final legislation.

“I’d warn people not to get overly exuberant about what we’ve seen in the last two months,” Vise said. “To some extent, it’s a function of ongoing disruption, the temporary lack of capacity, and the fact that we’re playing catch-up. It’s not sustainable and we’re not going to look at September and October as being a repeat of where we were in June and July.”